Valuing-Gemstones

Valuing Gemstones

Valuing colored gemstones differs significantly from valuing diamonds. While diamonds are graded according to a standardized system—the Four Cs (cut, color, clarity, and carat weight)—colored gemstones follow a more nuanced and less rigid approach. There is no single global grading system for colored gems, and value is often more subjective, shaped by a gem’s rarity, richness of color, treatment status, and origin. In many cases, color is the most critical factor, even more so than clarity or size. This makes the world of colored gemstones more diverse, but also more complex, and often more rewarding for those who appreciate uniqueness over uniformity.

The value of a gemstone is influenced by much more than just its name—it is shaped by a combination of factors including color intensity, clarity, size, geographic origin, and whether the stone has undergone any treatment. While some gems, such as alexandrite, tanzanite, and cobalt spinel, are inherently rare and command high prices due to their scarcity and unique optical properties, others like amethyst, citrine, or jasper are more abundant and therefore more accessible. Yet within each gemstone family, there is a wide range of value—fine-quality examples with vivid color, high clarity, untreated status, or prestigious origin can be many times more valuable than standard commercial-grade stones.

This range is perhaps most famously seen in the so-called “Big Three” precious gemstones: sapphire, ruby, and emerald. A rich, velvety Burmese ruby or an unheated Kashmir sapphire can command tens or even hundreds of thousands of dollars per carat, while lower-grade stones of the same type may be worth only a fraction of that. Similarly, a vivid green Colombian emerald with minimal inclusions can be exceptionally valuable, while more common, heavily included stones sell at much lower prices. Treatments such as heating in sapphires or oiling in emeralds are widespread and accepted within the industry—but untreated specimens with fine color and provenance are significantly rarer and more desirable to collectors.

Market trends and connoisseur demand also play a role in shaping value. Spinel, for example, was once overshadowed by ruby but is now gaining strong recognition, particularly in its red and cobalt blue forms. Ultimately, a gemstone’s beauty, rarity, natural integrity, and story all combine to determine its position in the hierarchy of value—whether it’s a treasured heirloom, a collector’s prize, or a personal indulgence.

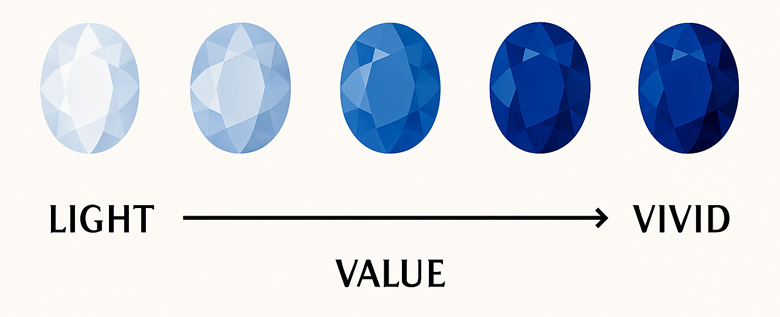

Vivid color indicates strong saturation and intensity, which is a primary driver of value in most colored gems.

For example:

A richly royal blue sapphire is far more valuable than a pale or overly dark one.

Deep green emeralds with vivid color fetch higher prices than light or grayish ones.

Intensely red rubies (especially “pigeon blood”) command top prices.

Value

Exceptions and nuances:

Too dark or overly inky colors can lower value — e.g., some sapphires or amethysts that are so dark they lose transparency.

Some stones are valued for pastel or soft hues (e.g., morganite, certain tourmalines).

Origin and clarity still matter: a vivid emerald full of visible inclusions may be less valuable than a slightly less vivid but cleaner one.

Treatments that enhance color (like heating or diffusion) can make a gem more vivid, but may not increase its value if the treatment reduces rarity.